This text was initially printed at The Conversation. (opens in new tab) The publication contributed the article to Area.com’s Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Michelle L.D. Hanlon (opens in new tab), Professor of Air and Area Legislation, College of Mississippi

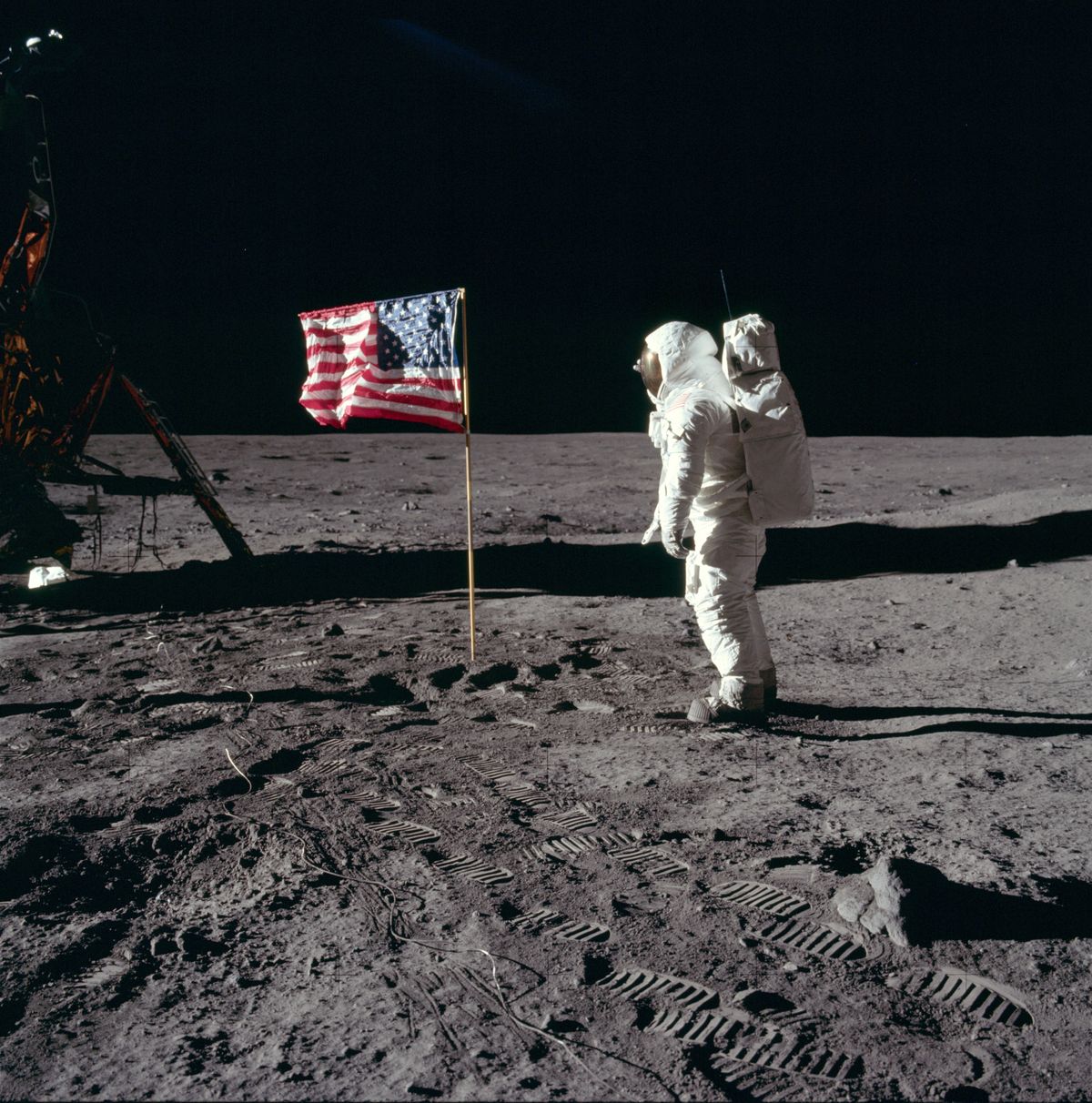

It has been 50 years since people final visited the moon, and even robotic missions have been few and much between. However the Earth‘s solely pure satellite is about to get crowded.

At the least six nations and a flurry of personal firms have publicly introduced greater than 250 missions to the moon (opens in new tab) to happen throughout the subsequent decade. Many of those missions embody plans for everlasting lunar bases and are motivated largely by ambitions to evaluate and start using the moon’s pure assets. Within the quick time period, assets can be used to assist lunar missions, however in the long run, the moon and its assets will probably be a important gateway for missions to the broader riches of the solar system.

Associated: NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission explained in photos

However these lofty ambitions collide with a looming authorized query. On Earth, possession and possession of pure assets are based mostly on territorial sovereignty. Conversely, Article II of the Outer Space Treaty (opens in new tab) — the 60-year-old settlement that guides human exercise in space — forbids nations from claiming territory in space. This limitation consists of the moon, planets and asteroids. So how will space assets be managed?

I’m a lawyer who focuses on the peaceful and sustainable use of space (opens in new tab) to learn all humanity. I consider the 2020s will probably be acknowledged as the last decade people transitioned into a really space-faring species that makes use of space assets to outlive and thrive each in space and on Earth. To assist this future, the worldwide neighborhood is working by way of a number of channels to develop a framework for space useful resource administration, beginning with Earth’s closest neighbor, the moon.

Lunar missions for lunar assets

The U.S.-led Artemis program is a coalition of economic and worldwide companions whose first objective is to return people to the moon by 2024. In the end, the plan is to determine a long-term lunar base. Russia and China have additionally introduced plans for a joint International Lunar Research Station (opens in new tab) and invited international collaboration (opens in new tab) as nicely. A number of personal missions are additionally beneath improvement by firms like iSpace (opens in new tab), Astrobotic (opens in new tab) and a handful of others (opens in new tab).

These missions intention to find out what assets are literally obtainable on the moon, the place they’re positioned and how difficult it will be to extract them (opens in new tab). At present, probably the most valuable of those assets is water. Water may be discovered primarily within the type of ice in shadowed craters in the polar regions (opens in new tab). It’s crucial for ingesting and rising meals, however when cut up into hydrogen and oxygen, it can also be used as fuel to power rockets (opens in new tab) both returning to Earth or touring past the moon.

Different worthwhile assets on the moon embody uncommon Earth metals like neodymium — utilized in magnets — and helium-3 (opens in new tab), which may be used to produce energy (opens in new tab).

Present analysis means that there are just a few small areas of the moon that comprise both water and rare Earth elements (opens in new tab). This focus of assets might pose an issue, as most of the deliberate missions will seemingly be headed to prospect the identical areas of the moon.

A dusty situation

The final human on the moon, Apollo 17 astronaut Eugene Cernan, referred to as lunar dust “one of the most aggravating restricting facets of the lunar surface (opens in new tab).” The moon is roofed by a layer of high-quality dust and small, sharp rock fragments referred to as regolith. Since there’s nearly no environment on the moon, regolith is easily blown around when spacecraft (opens in new tab) land or drive on the lunar floor.

Part of the 1969 Apollo 12 mission was to convey items of Surveyor 3 — a U.S. spacecraft that landed on the moon in 1967 to review its floor — again to Earth. The Apollo 12 lunar module landed 535 toes away from Surveyor 3, however upon inspection, engineers discovered that particles blown by Apollo 12 exhaust punctured the floor of Surveyor 3, literally embedding regolith into the hardware (opens in new tab).

It isn’t laborious to think about a lander or perhaps a floor rover of 1 nation passing too shut to a different nation’s spacecraft and inflicting vital harm.

A necessity for guidelines

As efforts to return to the moon started ramping up within the 2000s, NASA was so involved by the damaging potential of lunar dust that in 2011 it issued a set of suggestions to all space-faring entities. The objective was to guard Apollo and different U.S. objects on the lunar floor which are of historic and scientific worth. The suggestions implement “exclusion zones (opens in new tab),” outlined by NASA as “boundary areas into which visiting spacecraft mustn’t enter.” These recommendations are usually not enforceable towards any entity or nation except they’re contracting instantly with NASA.

The very idea of those zones violates the plain that means and intent of Article II (opens in new tab) of the Outer Area Treaty. The article states that no space of space is topic to “nationwide appropriation” by “technique of use or occupation.” Creating an exclusion zone round a touchdown or mining web site definitely could possibly be thought-about an occupation.

Nevertheless, the Outer Area Treaty does provide a possible resolution.

Worldwide actions

Article IX (opens in new tab) of the Outer Area Treaty requires that every one actions in space be carried out “with due regard to the corresponding pursuits of others.” Beneath this philosophy, many countries are at present working towards collaborative use of space assets.

To this point, 21 nations have agreed to the Artemis Accords (opens in new tab), which use the due regard provision of the Outer Area Treaty to assist the event of “notification and coordination” zones, additionally referred to as “security zones.” Whereas 21 nations is just not an insignificant quantity, the accords don’t right now embody the key space-faring nations of China, Russia or India.

In June 2022, the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (opens in new tab) fashioned the Working Group on Legal Aspects of Space Resource Activities (opens in new tab). This group’s mandate is to develop and suggest rules in regards to the “exploration, exploitation and utilization of space assets.” Whereas the group has but to handle substantive issues, a minimum of one nation not within the Artemis Accords, Luxembourg, has already expressed an curiosity in selling security zones.

This working group is an ideal avenue by way of which security zones like these outlined within the Artemis Accords might get unanimous worldwide assist. For All Moonkind (opens in new tab), a nonprofit group I based that’s composed of space specialists and NASA veterans, has a mission to assist the institution of protecting zones round sites of historic significance in space (opens in new tab) as a primary model of security zones. Whereas initially pushed by the annoying lunar dust, security zones could possibly be a place to begin for the event of a useful system of useful resource and territory administration in space. Such an motion would defend important historical sites (opens in new tab). It might even have the additional benefit of framing useful resource administration as a instrument of conservation somewhat than exploitation.

This text is republished from The Conversation (opens in new tab) beneath a Artistic Commons license. Learn the original article (opens in new tab).

Observe all the Skilled Voices points and debates — and develop into a part of the dialogue — on Fb and Twitter. The views expressed are these of the writer and don’t essentially mirror the views of the writer.