By Pam Longobardi, Georgia State University

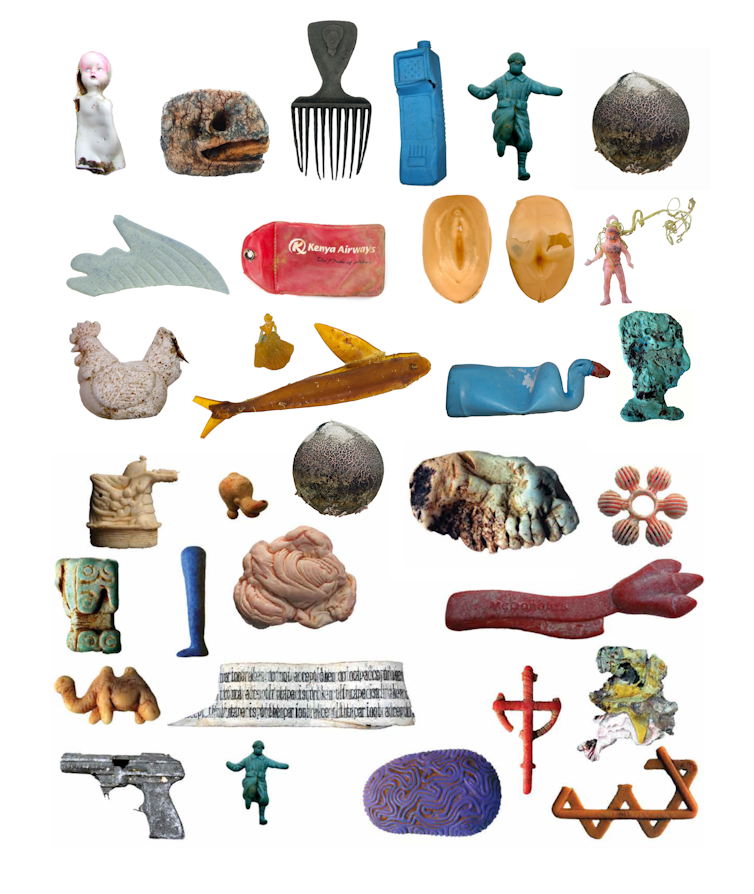

I’m obsessive about plastic objects. I harvest them from the ocean for the tales they maintain and to mitigate their capability to hurt. Every object has the potential to be a message from the ocean: a poem, a cipher, a metaphor, a warning.

My work amassing and photographing ocean plastic and turning it into artwork started with an epiphany in 2005, on a far-flung seaside on the southern tip of the Large Island of Hawaii. On the fringe of a black lava seaside pounded by surf, I encountered multitudes upon multitudes of plastic objects that the offended ocean was vomiting onto the rocky shore.

I may see that one way or the other, impossibly, people had permeated the ocean with plastic waste. Its alien presence was so huge that it had reached this most remoted level of land within the immense Pacific Ocean. I felt I used to be witness to an unspeakable crime in opposition to nature and wanted to doc it and convey again proof.

Last chance to get a moon phase calendar! Only a few left. On sale now.

Taking motion

I started cleansing the seaside, hauling away weathered and misshapen plastic particles. I collected recognized and unknown objects, hidden components of a world of issues I had by no means seen earlier than, and large whalelike coloured entanglements of nets and ropes.

Returning to that web site time and again, I gathered materials proof to check its quantity and the way it had been deposited, attempting to know the immensity it represented. In 2006, I shaped the Drifters Project, a collaborative world entity to spotlight these vagrant, translocational plastics and recruit others to research and mitigate ocean plastics’ affect.

Ocean Gleaning

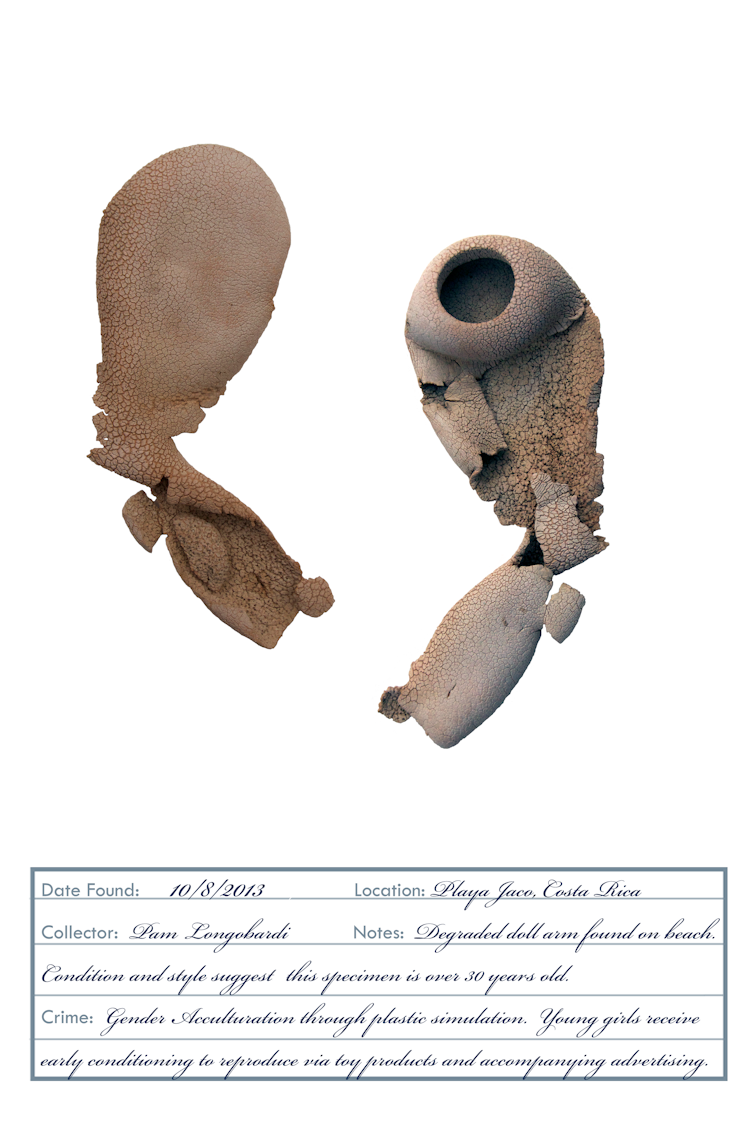

My new guide, Ocean Gleaning, tracks 17 years of my art and research world wide by means of the Drifters Mission. It reveals specimens of hanging artifacts harvested from the ocean. These are objects that after have been utilitarian however have been modified by their oceanic voyages and are available again as messages from the ocean.

Residing in a plastic age

I grew up in what some now deem the age of plastic. Although it’s not the one fashionable materials invention, plastic has had probably the most unexpected penalties.

My father was a biochemist on the chemical firm Union Carbide after I was a toddler in New Jersey. He performed golf with an actor who portrayed The Man from Glad, a Get Sensible-styled agent who rescued flustered housewives in TV commercials from inferior manufacturers of plastic wrap that snarled and tangled. My father introduced residence memento pins of Union Carbide’s hexagonal brand, based mostly on the carbon molecule, and figurine pencil holders of TERGIE, the corporate’s blobby turquoise mascot.

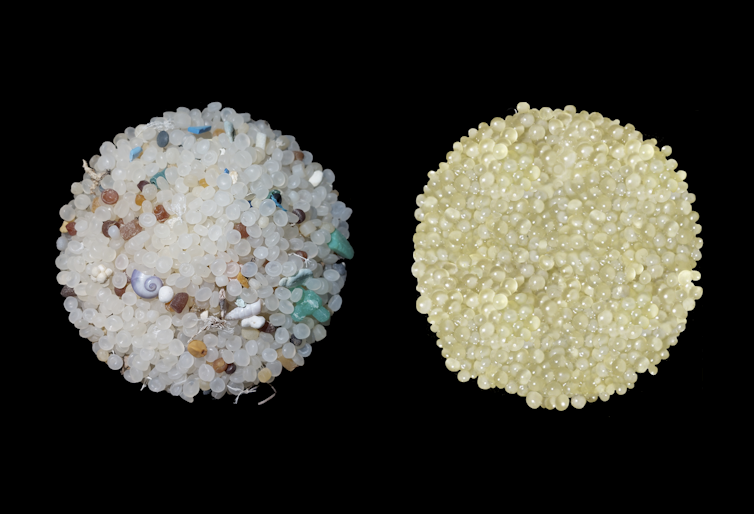

Ocean plastic is a zombie materials

At the moment I see plastic as a zombie materials that haunts the ocean. It’s created from petroleum, the decayed and remodeled life types of the previous. Drifting at sea, it “lives” once more because it gathers a organic slime of algae and protozoans, which grow to be attachment websites for bigger organisms.

When seabirds, fish and sea turtles mistake this dwelling encrustation for meals and eat it, plastic and all, the chemical load lives on of their digestive tracts. Their physique tissues absorb chemicals from the plastic, which stay undigested of their stomachs, typically in the end killing them.

The forensics of ocean plastic

I see plastic objects because the cultural archaeology of our time. They’re the relics of worldwide late-capitalist consumer society that mirror our needs, needs, hubris and ingenuity. They grow to be remodeled as they depart the quotidian world and collide with nature. By regurgitating them ashore or jamming them into sea caves, the ocean is speaking with us by means of supplies of our personal making. Some appear eerily acquainted; others are completely alien.

An individual partaking in ocean gleaning acts as a detective and a beacon, trying to find the forensics of this crime in opposition to the pure world and shining the sunshine of interrogation on it. By trying to find ocean plastic in a state of open receptiveness, a gleaner like me can discover symbols of popular culture, faith, battle, humor, irony and sorrow.

Artwork installations

Consistent with the drifting journeys of those materials artifacts, I desire utilizing them in a transitive type as installations. All of those works could be dismantled and reconfigured, though plastic supplies are almost not possible to recycle. I show some objects as specimens on metal pins, and wire others collectively to type large-scale sculptures.

Our ocean plastic trash reveals who we’re

I’m focused on ocean plastic particularly due to what it reveals about us as people in a world tradition, and concerning the ocean as a cultural space and an enormous dynamic engine of life and alter. As a result of ocean plastic visibly exhibits nature’s makes an attempt to reabsorb and regurgitate it, it has profound tales to inform.

I consider humankind is at a crossroads close to the long run. The ocean is asking us to concentrate. Paying consideration is an act of giving, and within the case of plastic air pollution, it’s also an act of taking: Taking plastic out of your day by day life. Taking plastic out of the atmosphere. And taking, and spreading, the message that the ocean is laying out earlier than our eyes.

Pam Longobardi, Regents’ Professor of Artwork and Design, Georgia State University

This text is republished from The Conversation underneath a Inventive Commons license. Learn the original article.

Backside line: Pam Longobardi creates artwork with ocean plastic to boost consciousness of the rubbish accumulating on the planet’s oceans.

Read more: Garbage in our oceans: How best to remove it?

![]()